Chinese scientists find that boosting NAD+ with its precursor, NMN improves the learning and memory of a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease.

Microglia cells stained for CD38, an NAD+ degrading enzyme | Hu et al., 2022

Highlights:

- Treating Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mice with NMN improves their learning and memory.

- NMN restores energy metabolism, reduces inflammation, and eliminates beta-amyloid, a hallmark of AD.

- Inhibiting an enzyme that degrades NAD+ called CD38 also reverses AD dysfunction.

While the accumulation of a protein called beta-amyloid (Aβ) is undoubtedly involved, the underlying cause of AD is still a mystery. And as the search for a cure continues, a new study published in Biological Research has shown that NAD+, an essential molecule needed to produce the energy of all cells, may play a key role.

In the study, Hu and colleagues from the Shanghai Geriatric Institute of Chinese Medicine reveal that boosting NAD+ reverses AD defects in a mouse model for AD. The researchers treated AD mice with either NMN, an NAD+ precursor that promotes the synthesis of NAD+, or a CD38 inhibitor (antibody). As an NAD+ degrading enzyme that increases with age, CD38 is considered the primary contributor to age-related NAD+ decline. The results showed that NMN or the CD38 inhibitor improve the learning and memory of AD mice and reduces inflammation, a hallmark of aging. Furthermore, boosting NAD+ decreases the prevalence of Aβ.

Boosting NAD+ Reverses Alzheimer’s Disease Defects

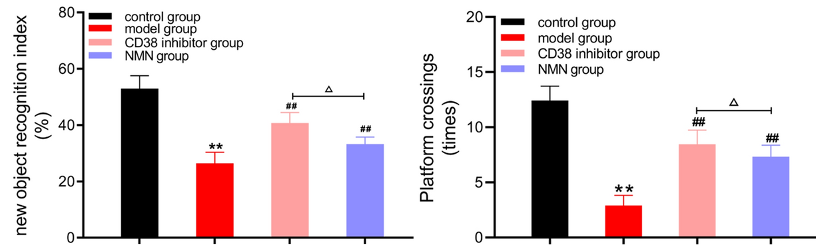

Demonstrating the cognitive deficits associated with AD, Hu and colleagues showed that AD mice perform worse on learning and memory tests than aged mice without AD. However, the learning and memory of AD mice improved after treatment with NMN or the CD38 inhibitor, suggesting that boosting NAD+ could improve the cognitive deficits associated with AD.

Microglia cells are responsible for degrading harmful brain material such as excess Aβ. However, this degrading process (phagocytosis and autophagy) is slow and promotes inflammation. Thus, if microglia cannot keep up with the production of Aβ, inflammation ensues without complete Aβ removal. To exacerbate it all, Aβ can inhibit this critical function of microglia, allowing inflammation to persist, and causing progressive damage to neurons, leading to neuron cell death (neurodegeneration) and cognitive decline.

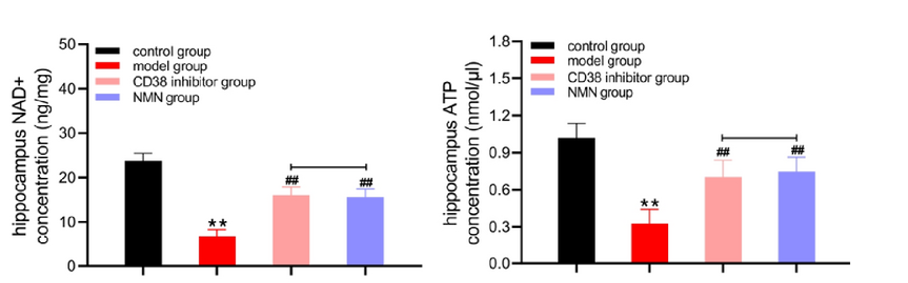

Maintaining the energy metabolism of microglia is essential for sustaining their Aβ-degrading function. NAD+ supports energy metabolism by facilitating the production of ATP, a molecule that cells use for energy. In aged microglia cells, low NAD+ and ATP make these immune cells less efficient or incapable of degrading Aβ. Thus, boosting NAD+ could increase the production of ATP, reviving the destructive power of microglia.

Hu and colleagues showed that NMN or CD38 inhibition increased the concentration of NAD+ and ATP in the brains of AD mice while reducing inflammation. These findings suggest that boosting NAD+ restores energy metabolism and reduces inflammation in AD mice, which could explain the observed improvements in learning and memory.

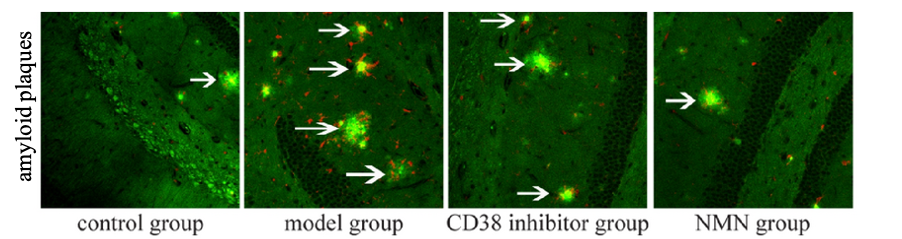

Microglia cells take different forms; in their active form, they become harmful and produce inflammatory molecules. Hu and colleagues showed that boosting NAD+ reduces microglial activation and eliminates Aβ from AD mouse brains. These findings suggest that increasing NAD+ levels restores the destructive capacity of microglia cells, enabling them to rid the brain of harmful Aβ deposits.

Can Boosting NAD+ Treat Alzheimer’s?

Overall, the findings of Hu and colleagues suggest that boosting NAD+ by inhibiting CD38 or supplementing with NMN revives aged microglia cells, allowing them to destroy Aβ and reduce inflammation in AD mice. This reduction in inflammation could lead to improvements in learning and memory. Another study showed that genetically removing CD38 can improve the memory of AD mice. Furthermore, boosting NAD+ with another precursor, NR, has been shown to reduce neuroinflammation, possibly leading to improved cognitive performance. Indeed, a recent study showed that reducing inflammation with a molecule called saikogenin F improves the learning and memory of AD mice.

While these animal studies make boosting NAD+ seem like a promising treatment for AD, there are not enough human studies to validate the findings. For example, a recent study showed that while NR and caffeine raise NAD+ and ATP levels in cells cultured from AD patients, it does not improve metabolic parameters. However, it is unclear from this study whether NR and caffeine could improve cognitive performance in AD patients. Thus, the effect of boosting NAD+ on cognitive performance in AD patients still needs to be tested, but the prospects seem promising.